The gold jewellery created from previous phones

A chemical option

E-squander (also identified as waste electrical and digital machines or WEEE) is the world’s fastest-growing squander stream. In accordance to the United Nations Environment Programme, an estimated 50 million tonnes of e-waste is manufactured globally each individual 12 months, weighing more than all of the commercial airliners at any time built. But only 20% of that is formally recycled, and most will get thrown away and either despatched to landfill or incinerated. Very last yr a analyze by price tag comparison provider USwitch located that the Uk produced the second greatest total of e-squander per human being, with Norway position best and the US in eighth position.

As demand from customers for far more portable products and rapidly electronics grows, so also will the e-squander mountain. In 2019, the Globe Economic Discussion board estimated that by 2050, once-a-year e-squander creation will additional than double to 120 million tonnes.

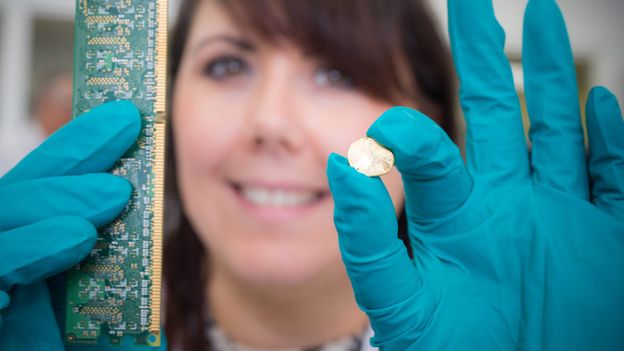

Like all crucial raw supplies, gold is a finite useful resource, but 7% of the world’s gold is at present sitting down in disused electronics. Gold extraction normally entails exporting units to the EU or Asia wherever e-squander is smelted down at very significant temperatures in a extremely crude and carbon-intense system.

“We want to recover as a lot of the precious metals as we can from matters which are at present waste,” states Messenger. “Our target is on executing this sustainably within the Uk, applying a process that’s effective at place temperature although developing a great deal much less greenhouse fuel emissions than smelting.”

“If we’re manufacturing the waste, it must be our responsibility to kind it, we should not be shipping it to yet another country to form it for us,” suggests Mark Loveridge, professional director at the Royal Mint. He suggests that building e-squander offer chains close to localised recycling plants would considerably reduce the waste miles needed to transport discarded electronics by sea, air and highway, and the Royal Mint is previously in talks with partners all-around the world with the ambition to globalise this technology.

You might also like:

Swapping my lab coat for an orange difficult hat, large-vis jacket and black, steel-toe-capped boots, I head to the new processing plant. Dozens of large dumpy baggage are stacked up in the much corner of this 3,000 sq m (32,292 sq ft) factory, every single filled with colourful circuit boards. These have been taken out from laptops and cell telephones, and shipped to the factory by a community of 50 e-waste suppliers about the place.

On arrival, circuit boards are inspected and tipped into a massive silver hopper which funnels this uncooked content into a huge multi-colored equipment. Tony Baker, director of production innovation who is overseeing the installation of this plant, describes that as circuit boards get mechanically separated and damaged up, any non-gold factors are held to 1 facet, even though any gold-bearing parts these types of as USB ports are digitally detected and despatched to a 500-litre (110 gallon) reactor. Right here, the “magic environmentally friendly option” will get added on a significantly much larger scale, gold sand is extracted and, once again, nuggets are made.

For the reason that so a great deal non-gold is taken off at the start out, the chemical processing is only applied to fragments made up of gold, as Baker clarifies. The uncooked materials used by the Royal Mint is comprised of circuit boards, alternatively than total laptops or entire cellular telephones. After the gold has been extracted, the leftover non-gold parts are all despatched off to different sections of the offer chain for reuse, so practically nothing will get wasted. The gold information differs among 60 areas for each million to 900 parts for every million, relying on the feedstock, in accordance to Loveridge.